This is an opera you hear talked about sometimes, so I was glad to get to see it. It wasn't actually performed in 1968; it was scheduled to be, but was cancelled for being too "controversial" (though the DVD does include an introduction from 1974 written for the publication of the score by none other than Dmitri Shostakovich). Of course: the fact that "the Holocaust was bad" was apparently a controversial statement. It was going to be performed in Russia, where you'd think that wouldn't have been the case, but what do I know?

The "present-day" of the piece is the early sixties. A woman named Liza is on a ship headed for South America, where her husband Valter has a diplomatic posting. She freaks out when she sees a woman who, she becomes convinced, is actually Marta, a Polish woman who was a prisoner when she was a concentration camp guard. Most of the story takes place at Auschwitz in flashback. Marta was known as the "Madonna of the camp," always doing her best to help other prisoners. She also had a fiancé there, Tadeusz. We see the prisoners--there are quite a few of them, very vividly depicted--and Tadeusz, a violinist, commits a small act of rebellion when, ordered to play the Commandant's favorite waltz, he plays something else, and is taken away and killed. We never learn exactly what happens with Marta, even whether she's really the woman on the ship, but in the final scene, we do see her alone on stage in civilian clothes, her hair grown back out, singing about the importance of remembering the dead, and that she'll always keep Tadeusz in her heart.

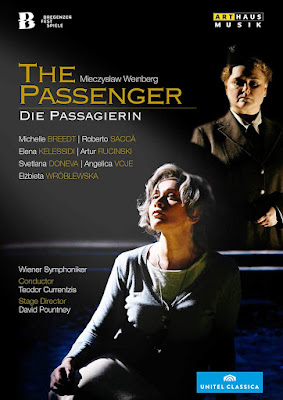

One definitely should not feel any sympathy for Liza, who is a real piece of shit. I'm not saying that people who do horrible things can't be redeemed, but it's pretty obvious that what she feels is closer to social embarrassment than actual guilt. She tries to justify herself by claiming that she was nice to the prisoners, but as we see, she really just wanted them to like her and feel gratitude towards her, and was off-put when they didn't appear sufficiently grateful. And, of course, she passively let Tadeusz die so, you know. If she's not in the worst ten percent of the Nazis, it's only because the competition was so fierce. Even her douchebag husband--who, it is very clear, is only upset about her past (which he hadn't known about) because he thinks it will negatively impact his career--is less unpleasant than she is (which, however, is not a knock on Michelle Breedt, who acts the hell out of the role).

The music is very dramatic, occasionally discordant, in a way that might indeed recall Shostakovich. I liked it very much, in spite of the harrowing subject matter. Weinberg seems like a composer who deserves more recognition (this was the first of seven operas he wrote).

I know there's some argument about whether it's even possible to create art about the Holocaust that isn't in some way exploitative. But even if you can, it might further be argued that a highly aestheticized art form like opera is the wrong way to do it. And really, what can you even SAY about it at this point?

Well, be that as may, I thought this worked extraordinarily well. Marta is a really impressive character, and the everyday horror of the Holocaust is certainly brought home, in scenes with prisoners speculating on their probably deaths and forlorn hopes for the future. Just thinking about it is chilling. But somehow, what really got to me more than anything else was a scene in which a cart of confiscated violins is wheeled in (the Commandant, as noted above, being a music buff). Violins. Could anything emphasize more clearly the dignity and humanity of the people you're setting out to murder? Treated totally casually by the Nazis, of course.

You should see this opera.

No comments:

Post a Comment