This is Cavalli's last extant opera. He wrote two others after, but they are...not. I suppose you can't complain too much; compared to many of his contemporaries, he does pretty well in the extant-operas department, but STILL: his final opera, Masenzio, is especially a bummer, because wikipedia lists it as "unperformed and lost." So Cavalli created this art and nobody ever experienced it and now nobody ever will. Pretty disheartening. Still! We're lucky to have this one, which went unperformed in Cavalli's day also, because, Wikipedia speculates "Cavalli's style was considered too old-fashioned." My friend--Cavalli will NEVER go out of style. But in any event, it was first performed in 1999. There's a time lapse for you.

Heliogabalus doesn't get the same press as Caligula or Nero in the nuttily psychotic emperor sweepstakes, but he was apparently pretty well up there. But...give him a break. He became emperor at the age of fourteen (and was assassinated at eighteen). YOU try making a fourteen-year-old the most powerful person in the world and see how that works out. There's a famous story about how he murdered some guests at a banquet by smothering them with roses. This is depicted in a painting by Lawrence Alma-Tadema, The Roses of Heliogabalus:

It's an appealingly macabre idea, but would it actually be possible? If so, you'd need an absolute shit-ton of roses, and I imagine you'd have to pack them down really tightly. I can't help noting that the people allegedly dying in the painting don't even have their heads submerged. That's not gonna do the job!

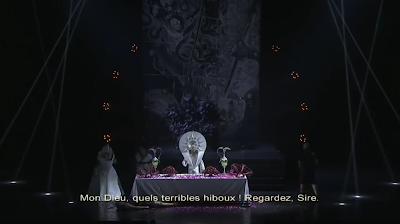

Anyway! As for the opera: there's a production with French subtitles on youtube. With star countertenor Franco Fagioli in the title role! Again, I am utterly baffled as to why this hasn't been released on DVD/blu-ray. So as usually with these things, the plot is a bit shambolic, but basically: there's just been a military uprising, because the army hates Eliogabalo. But it's been put down by his...associate emperor?...Alessandro (who would become the main emperor after Eliogabalo's death, only to be assassinated himself so that the most terrifyingly-named Roman emperor, Maximinus Thrax, could take power. So it goes!); the army LIKES him. Alessandro wants to marry his sweetheart Gemmira, but the dissipated emperor decides that he wants her instead (without even having seen her). So he comes up with various plans make this work. He comes up with a weird idea to start a "congress of women" (this is based on actual historical incident, big fat "allegedly), so he can go in drag and get with her; when this fails, he decides to have a banquet where Alessandro will be given poison and Gemmira opium so he'll be out of the way and he can have his way with her. There's also another couple, of course, this being Eritea, a woman that Eliogabalo has previously loved and left, and Gemmira's brother Giuliano. Theyre all sort of dithering around thinking about how or whether they should assassinate the emperor, and finally--this might actually constitute a spoiler; it certainly took me by surprise--Eliogabalo is beheaded while he's trying to rape Gemmira. Even more surprising than that is that his hanger-on Zotico and the flippin' comic-relief skirt-role nurse are ALSO killed, by an angry mob! My goodness! I mean, yes, they've aided and abetted Eliogabalo, but still. That's not the kind of thing you expect to see in a baroque opera. And for the sake of completeness, there's also another woman, Atilia, who is in love with Alessandro and causes some complications but then at the end is just like, welp, easy come easy go, I'll find someone else; and also this comedy amoral gold-digger Nerbulone, who goes for any woman with money. Oh, and also, there's a scene at the end of the second act where the banquet hall is invaded by owls--birds of ill omen, apparently--and it features the line "My God, what terrible owls!" So that's a lot of fun.

This opera fucking rules, as we've come to expect from Cavalli. I hardly know what more to say. Fagioli makes a fabulous, glammy Eliogabalo--not exactly a deep character, but surely a fun one to play--and Nadine Sierra is a righteous and beautiful Gemmira. Also notable is Scott Conner as Nerbulone; it's a small role, but I'd never seen him before, I don't think, and his bass is extremely booming.

Cavalli certainly has his fans, but I can't help feeling that he is one of the most underappreciated composers around. The Met has never performed a seventeenth-century opera--amazing but true--and he would certainly be a good place to start.